Being involved in different projects where web technologies are used, I have to make sure that AppSec related security nightmares are avoided. One of those security nightmare - and in my own oppinion the most complicated one to explain to a non-sec person - is CSRF. I won’t go into details since these are freely available. Furthermore I would like to focus on the countermeasures one would implement to prevent CSRF. In some cases it’s suggested to think of some attack scenarios before relying on the implemented solution. But first let’s have a look how a typical CSRF attack works like.

General idea

Usually we have 3 components involved:

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

Attacker;

Client [label="Client/Browser"];

Server;

}

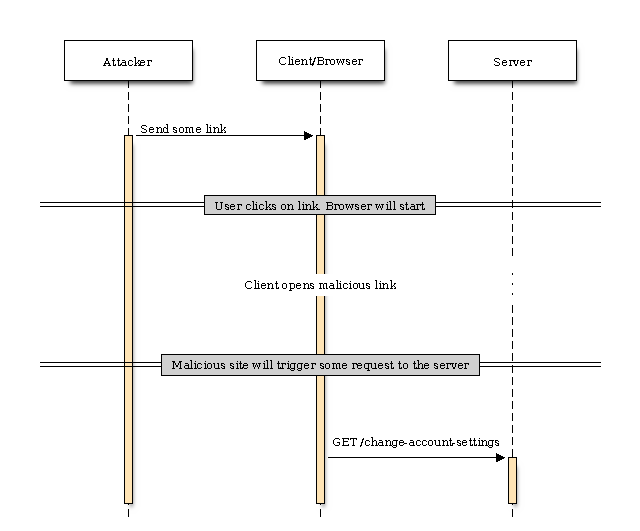

The client/browser communicates with the server and the attacker will try to lure the user to some previously prepared site. This can happen by sending mails with some malicious link or injecting content into a site the user is visiting (e.g. using iframes). This way the attack will cause the client/browser to fire requests to the server without any user interaction. The user behing the client/browser won’t notice anything since this will happen in the background by just visiting the site and/or triggering some JavaScript to execute.

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

Attacker;

Client [label="Client/Browser"];

Server;

Attacker -> Client [label="Send some link"];

// Separator

=== User clicks on link. Browser will start ===

... Client opens malicious link ...

// Separator

=== Malicious site will trigger some request to the server ===

Client -> Server [label="GET /change-account-settings"];

}

Some example

Now let’s think of some real-world example. User Bob has an account on http://bank.nu. Attacker Victor will prepare a site http://attacker.nu which once accessed will load following iframe:

|

|

In this case the iframe ins’t visible at all (display:none) and some JavaScript will trigger the submission of the form once the scripttag is loaded aka the user enters the site. In this fictional example the form will trigger a POST request which will transfer some money to the attacker (Victor). Next the attacker will send Bob a mail with a link to his site http://attacker.nu. Bob will click on this link and the browser will open the link. Untill now nothing happens. Once the browser will load the attackers site, the whole voodoo behind CSRF would take place.

CSRF fundamentals

At this point I’d like to slow down things a little bit and focus on some details. In the past people have asked me some questions or made some observations regarding the whole process. Among these (I tried to apply the questions/observations to the previous example):

- “In a iframe you are able to load stuff (javascript, images etc.) via GET. How do you trigger a POST request at all?”

- “The attackers site is not authentificated to

http://bank.nu. Your triggered request is not going to work at all.” - “Why should the browser trigger the request once the user visits the attackers site?”

- “We do protect the session cookies by

httponlyand thesecureflag. Why do you think this is going to work?”

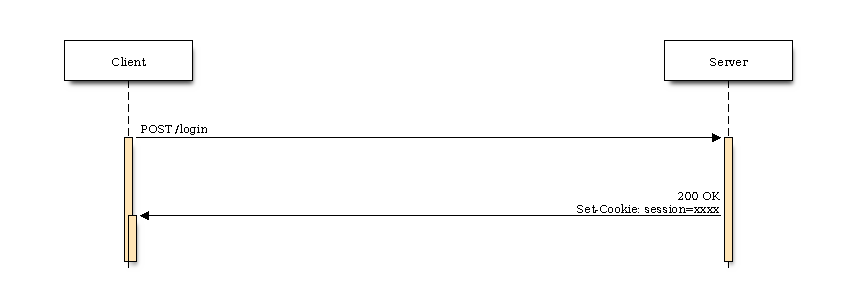

Well first let’s see why this kind of attacks are so powerful. Apparently Bob can only trigger the transaction if he has a valid session. Otherwise the bank would show some error message that the request is not allowed and a valid session is necessary. The authentification process usually looks like this:

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

edge_length = 600;

Client

Server;

Client -> Server [label="POST /login"];

Server -> Client [label="200 OK\nSet-Cookie: session=xxxx"];

}

The user sends his credentials to the server, the server validates these and sends a cookie to the client which serves as authentification characteristic. Regardless of the expiration time of the cookie, every time the browser/client makes a request to the server, the cookie will be sent automatically to the server. This is a very important one and often misunderstood by non-sec people.

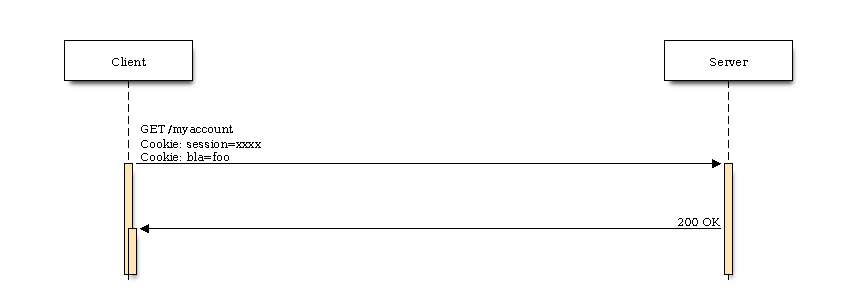

So next time the user wants to visit the site again, the browser will add the cookies received from the server to the request:

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

edge_length = 600;

Client

Server;

Client -> Server [label="GET /myaccount\nCookie: session=xxxx\nCookie: bla=foo"];

Server -> Client [label="200 OK"];

}

That in turn means that every time a request is conducted by your browser - whether intended by the user or not - the session cookie will be always be sent along with the request.

The attack

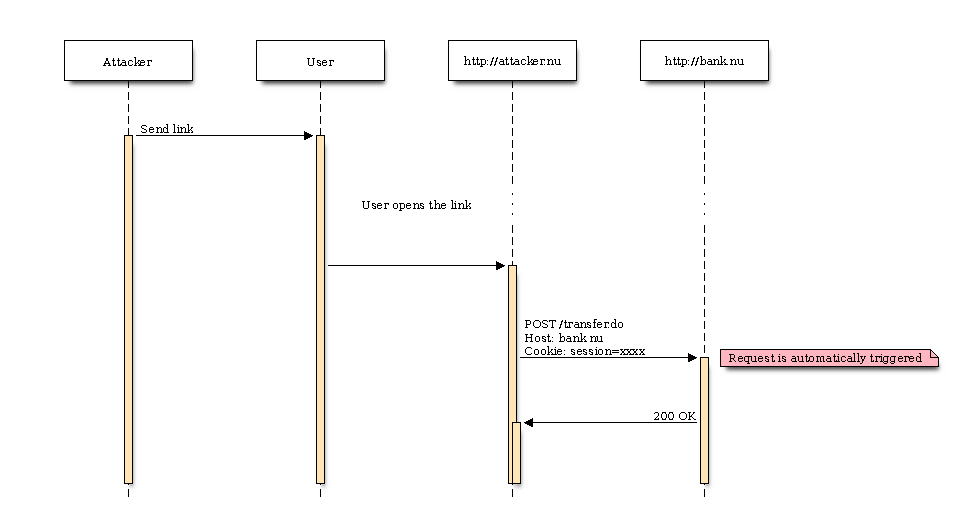

Recalling a few thoughts made some sentences ago, the attack will consist of following steps:

- Send a malicious link to Bob

- Bob will click the link and the browser will open the malicious site

- The malicious site will trigger a POST request to

http://bank.nuand try to make a money transfer - This is going to work only and if Bob is logged in (has a valid session cookie) on the bank site

Trying to be more precise, these are the requests made:

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

Attacker;

User;

Site [label="http://attacker.nu"];

Bank [label="http://bank.nu"];

Attacker -> User [label="Send link"];

... User opens the link ...

User -> Site;

Site -> Bank [label="POST /transfer.do\nHost: bank.nu\nCookie: session=xxxx", note = "Request is automatically triggered"];

Bank -> Site [label="200 OK"];

}

As you have noticed the session cookie is part of the POST request. The attackers site can’t read the cookie due to several reasons:

- the domain attribute of the cookie restricts the availability of the cookie only to the

bank.nudomain- that means that the browser will only set the cookie if the request is made to

bank.nu

- that means that the browser will only set the cookie if the request is made to

- the httpOnly flag is set

- no JavaScript can read the cookie

But the attacker doesn’t have to know the cookie. In the case of CSRF he/she will fire up a request assuming that the victim is authentificated against bank.nu. If not, the

attack will have no consequences since the POST request won’t be accepted by the server.

The defense

Since it is the natural behaviour of the browser to add the cookies to some specific requests (in order to tell the server that the user is authentificated), the mitigation of such attacks has to be done somewhere else. The generic solution consists of adding some random secure token which has to be:

- unique per user/session

- tied to only one session

- generated by a secure PRNG

The client has to provide this token in its requests. The server will reject the request/action if the token is not valid. Sounds simple, isn’t it? There are two ways to do it:

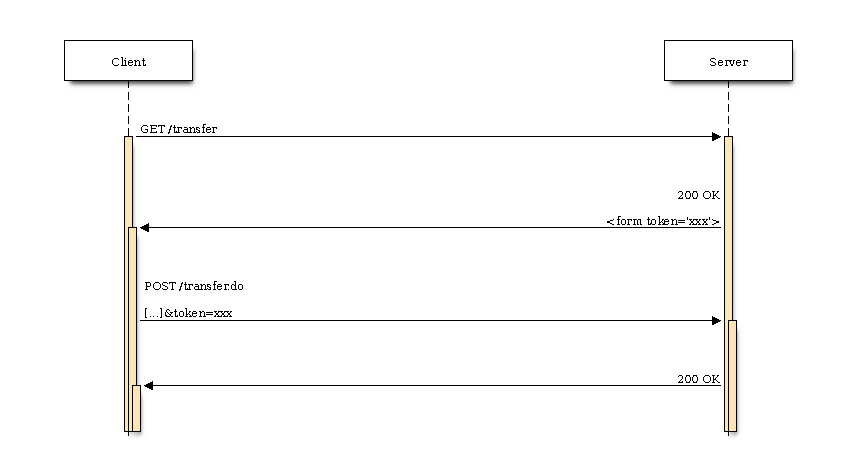

Provide the token in a hidden field (Synchronizer Token Pattern)

If the client wants to perform an action (like sending a POST request), the server will put inside the body content a hidden token which the client has to provide when sending the POST request:

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

edge_length = 600;

Client -> Server [label="GET /transfer"];

Server -> Client [label="200 OK\n\n<form token='xxx'>"];

Client -> Server [label="POST /transfer.do\n\n[...]&token=xxx"];

Server -> Client [label="200 OK"];

}

The token should change every time the site is loaded again. That means that the server should not accept 2 POST requests with the same token value.

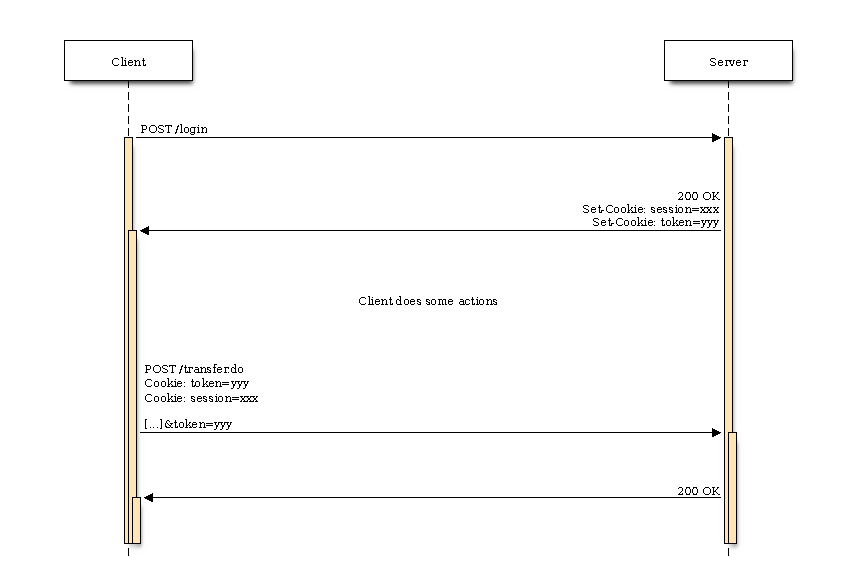

Provide session based CSRF token (Double Submit Cookies)

Once the client has authentificated against the server, the server will send the client a CSRF token which will be used for every request. The token value doesn’t change and remains the same for the whole session.

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

edge_length = 600;

Client -> Server [label="POST /login"];

Server -> Client [label="200 OK\nSet-Cookie: session=xxx\nSet-Cookie: token=yyy"];

... Client does some actions ...

Client -> Server [label="POST /transfer.do\nCookie: token=yyy\nCookie: session=xxx\n\n[...]&token=yyy"];

Server -> Client [label="200 OK"];

}

The interesting thing about this approach is the fact that the token is sent twice. The CSRF token is being sent to the client as a cookie. That means that this specific cookie will be sent automatically by the browser when some requests are triggered (natural behaviour, remember?). At first look this approach doesn’t look secure, since the session cookie and the csrf token will be sent automatically by the browser in case of a forged request. Remember that the attacker doesn’t have to know the cookie values. He/she just forges the request and since the server can’t distinguish between a legitimate and a forged request, the attack will be successful.

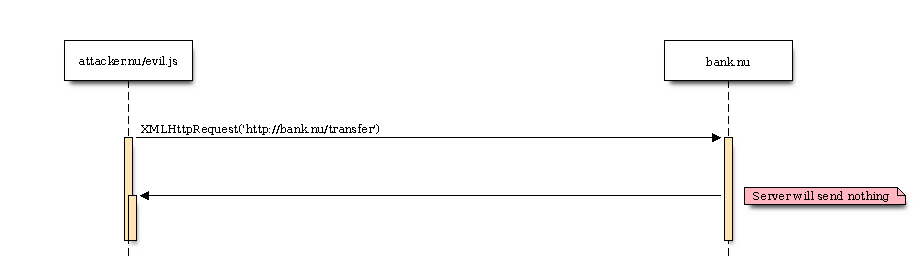

However, in the Double Submit Cookies approach the token value has to be sent more than once: Either as a GET or POST parameter. So the big question here is: Why is this secure? Well due to the fact that the token value has to be submitted somewhere else, the attacker will have to read this value - which is not possible. The attacker can forge the request but he can’t get the response. The reason therefore is called SOP (Same Origin Policy) and prevents cross-requests (aka from other domains) to be performed. In our case a script hosted at attacker.nu would not be able to get “ressources” from bank.nu when executed in the browser.

blockdiag code

seqdiag {

edge_length = 600;

attacker [label="attacker.nu/evil.js"];

server [label="bank.nu"];

attacker -> server [label="XMLHttpRequest('http://bank.nu/transfer')"];

server -> attacker [note="Server will send nothing"];

}

This is the reason the attacker can’t read the token value even though he is able to forge requests. Providing the token value twice make this approach secure since the attacker can’t read the token value and therefore can’t forge a valid request (accepted by the server).

Conclusion

There are some other patterns I’m aware of (there might more!):

But the most valuable “take-home-lesson” is not about the technical details regarding the solutions. When discussing solutions several things should be always considered:

- The browser will always send available (regarding to the domain) cookies within the requests (whether its a page, JS, CSS, JPG whatever)

- If XSS is possible, you have bigger problems

- SOP offers no protection anymore

- Make sure the CSRF token is random and unique per session

- When storing the CSRF token as a cookie, make sure you double check the value

- The client has to provide the token as a GET/POST parameter

- Don’t rely on the validation based on the cookie